|

At the ASIS&T Annual Meeting 2023 I will be presenting a poster based on one of the contributions of my PhD. Specifically, I'll be presenting on a novel way to determine trustworthiness in qualitative research: community validation. The name of the method is just a description of what I felt I conducted at the time, though if someone asks I can go down a rabbit hole of whether I now think the word validation is appropriate and/or if it gives a false impression of what the method can and can't do. However, I don't think you are here to read about that, and it is perhaps better as a topic of conversation rather than the topic of a blog post. At the ASIS&T poster presentation session my poster as well as some handout sheets will be available. In fact, you may have made it to this page because you followed the QR code on the poster. If that's the case, please do ask me some questions in person but also feel free to download the handout sheet or a digital image of the poster at the end of this post. At the presentation I'll give a brief run-through of how community validation can address some of the limitations of two classic methods of determining trustworthiness. As a sneak peek, community validation addresses these limitations by leaning into them in order to increase interpretive power of the results (warning: the method should probably only be used within particular research paradigms). I think there is still some work to be done on the method as a whole, but hope that it can be used by researchers in the future to dig deeper into their results. The development of community validation as a method stemmed from the limitations of my initial data collection, caused in part by COVID-19 complications, where there were difficulties connecting with the community of interest. As a result, my initial work was focused on information gatekeepers of that community. The community validation was a way to ensure that I still made a place in my findings where the voices of those who are marginalised could be highlighted, and that is another strength of the method compared to other classical methods. Research with gatekeeper communities in place of (or addition to) the communities of interest are sometimes necessary, particularly in Library and Information Science (LIS) research. Community validation can be particularly useful in these situations, and I hope that it will be useful to other researchers and practitioners in the future. I end with a big thank you to Dr. Frances Ryan for helping me organise my poster in a way that catches the eye. Keep apprised of this space later this week for updates on my presentation and to learn about what information scientists get up to in London!

0 Comments

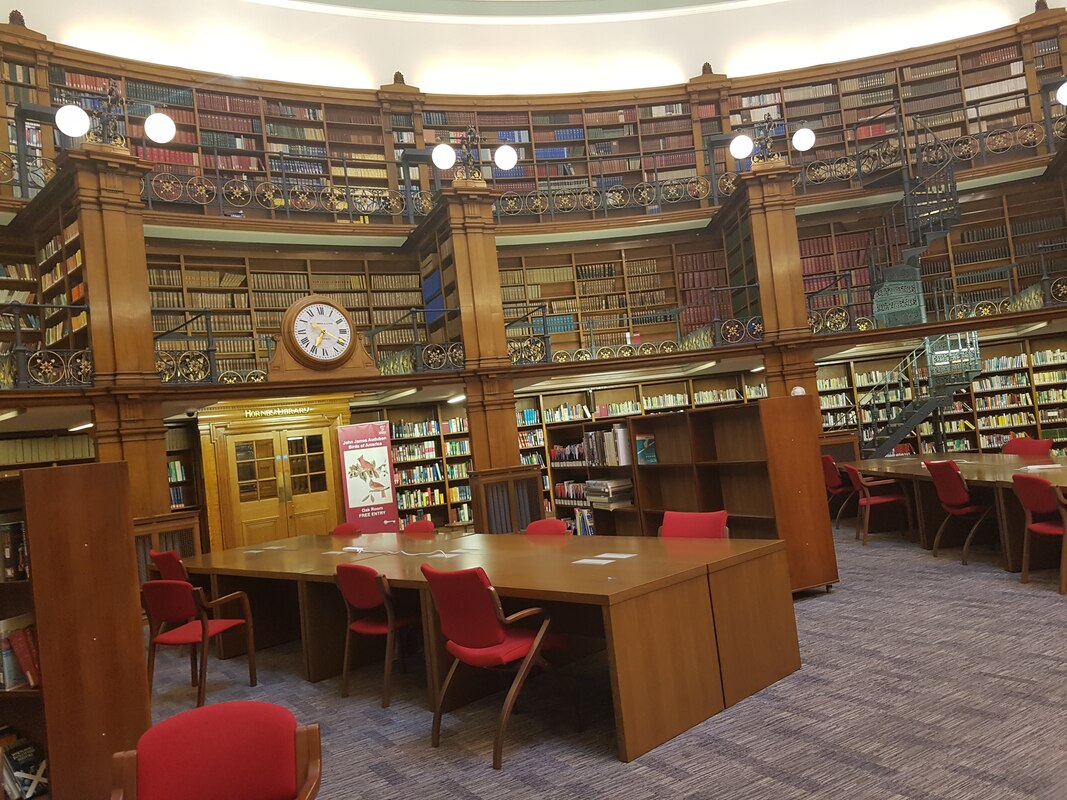

As a student in the field of library and information science, I have been a member of CILIP since the beginning of my degree. However, I haven't had a chance to attend their annual Conference + Expo until this year (the global pandemic put a few wrenches in those plans). This year that changed though! Thanks to a bursary from the Library and Information Science Research Group (LIRG) at CILIP I was able to attend the full Conference + Expo in Liverpool this year from July 7 to July 8. And as a bonus I managed to get a "We Are CILIP" selfie at the CILIP booth in the exhibit hall (see above). Though the exhibit hall and sessions officially opened on July 7, those of use who were in Liverpool by the evening of 6th were able to enjoy a dinner and afterhours tour of the Central Library (picture of the reading room below). As someone who always wanted to be "locked in" at a library overnight, it was a pretty awesome experience to see the library when users weren't there. On July 7, the conference began with coffee/tea and a powerful keynote by Sayf Al Ashqar from Iraq. The keynote was accompanied by a poem from Vanessa Kisuule about the importance of libraries. A whirlwind of exhibit exploration and conference sessions followed, with a chance to win a prize if you visited every booth in the exhibit hall (I didn't win, unfortunately, but good conversations were had overall). One of my favourite sessions on July 7 was the launch of the Green Manifesto, where panel members shared ways that their libraries were working on their environmental goals. The Green Libraries programme, beginning in February, is meant to help libraries reduce their carbon footprint and support their communities to do the same. The work that libraries are already doing was quite interesting to hear about, and hopefully the programme will help many more libraries reach their environmental goals. The day ended with a drinks reception at the Museum of Liverpool that evening. Though I wasn't able to attend (I spent some quality time with friends I hadn't seen for a while) I heard that it was a great time for those who did.

July 8 the day began with more coffee and a keynote by Professor Jacqueline McGlade about connected knowledge and the ways information professionals can help the world address climate change. Though there were many things to take away from this keynote, one that was especially powerful to me was the multiple shapes information and knowledge takes. This connects with a concept a participant brought up in my own PhD research and is something that I want to be able to explore more fully in the future. It also connects with other keynotes from an earlier conference this year: Conceptions of Library and Information Science. All in all, I haven't yet ruminated on it enough myself, but hope to be able to explore the many forms of information and knowledge and their relationships with migration/colonisation/assimilation/integration. But the keynote wasn't the only interesting session on day two. I attended three sessions on July 8, Working Towards Net Zero, Better by Design (based on a book now available from Facet Publishing), and Allyship in Action. Though each of these sessions was interesting, I was able to take the most away from Allyship in Action. Allyship in Action had a short presentation at the beginning about the importance of being an ally, but the majority of the session was spent in small groups where we discussed amongst ourselves the qualities of an ally and the challenges of becoming/being an ally. At the end, everyone was challenged to commit to actions that they would do going forward to continue on their allyship journey. This session was motivating, and I am very glad that it was offered at the conference. Overall, my experience at the CILIP Conf+Expo was awesome and I suggest that all information professionals look into attending. I'm sure some years will be more aligned with certain needs, so people may not feel the need to attend every year, but even just the networking is a great opportunity so if there is the chance to go, take it. I also suggest applying to the many bursary options. I got the one from LIRG this year, but I know there were also other opportunities that gave people the chance to attend when they otherwise wouldn't have. So keep apprised of the conf+expo and when the programme matches your interests and stay alert for those bursary opportunities! Deadlines are an element of the majority of work today. Whether this is a deadline of nature (if you leave harvest until after the frost the harvest risks being inedible) or a deadline constructed by work (complete this paperwork/task by this date) or a deadline for an assignment from a form of education (your paper for the assessment is due on this date at this time), deadlines permeate the human experience. And yet, often the deadlines we must meet are one of the greatest sources of stress that we have. Now as many people have probably heard, stress in small doses can enhance performance. Perhaps you notice more things, or you're able to physically complete more than you would have otherwise. Of course, we've also probably heard about this stress being bad for our bodies over long periods of time, messing with our sleep and health.

So what about deadlines, these borders drawn to indicate temporal constraints? Are they necessary to our work? Do they do more harm than good? We are trained to work with deadlines from childhood, and in some ways the world itself is built on deadlines. After all, what is death but not a deadline? It's a morbid thought, but still an argument that can be made. If deadlines are natural, then surely they are good (as many advertisments for products that say "all-natural ingredients" will posit)? I think it's a little more complicated than good and bad, as most things are. Human beings tend to feel better when there are clear boundaries, at least when those boundaries are perceived as fair and reasonable. In fact, there have been studies on how too much choice actually results in more difficulty choosing (e.g. Chernev, 2003). The boundaries on how many choices we have actually helps us make a decision. I think that similarly, working with deadlines can also help us actually complete work. The boundary is useful. To an extent. Deadlines have been shown to help us to meet goals and complete projects (e.g. Katzir et al., 2020), but sometimes those deadlines seem to hinder more than help. Part of this has to do with motivation. Amabile et al. (1976) found that external deadlines can decrease intrinsic motivation, leading to deadlines that "may also prove ultimately dysfunctional and even selfperpetuating". So deadlines can be good and give us a goal to reach, potentially increasing the motivation to actually complete a task. But they can also have a negative affect on intrinsic motivation and simply be pushed further and further off. As seen in the comic at the top of this page (from PhD Comics, which is one of the joys I have found during this PhD), deadlines are often pushed further and further down the line because it is so difficult to make them. So which is it? Are deadlines helpful or harmful? In my PhD experience, it matches the literature, which says the answer is both. Deadlines can be helpful, because they mean I can see the "end" of my PhD. I know that by a certain point I will be expected to have everything written, turned in, and at that point I can actually sleep through the night without a "finals nightmare". But...PhD's are stressful in part because they help prepare future researchers for the inevitable delays and barriers that come up during research. These delays mean that deadlines can actually be a big hindrance because I feel like I can't meet my deadline when I haven't had a chance to complete the thing because I'm trying to conduct research in the middle of a global pandemic (ahem, as an example). So my take on the deadlines is that they are a somewhat necessary evil, and that the systems around us should be taking into account the fact that natural deadlines (returning to the concept of frost) don't work the same way as deadlines imposed in the workplace. Workplace deadlines can still be made, but maybe they don't need to be as "ride or die" because they shouldn't have to be. Let us rest, and set up systems in ways that resting doesn't make us more stressed "because the work is still there when I get back". References: Amabile, T.M., DeJong, W., & Lepper, M.R. (1976). Effects of Externally-Imposed Deadlines on Subsequent Intrinsic Motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 34(1), 92 - 98. dx.doi.org.napier.idm.oclc.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.1.92 Cham, J. (2015). Academic Deadlines. PhD Comics. www.phdcomics.com/comics/archive/phd072915s.gif Chernev, A. (2003). Product Assortment and Individual Decision Processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85(1), 151 - 162. psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.151 Katzir, M., Emanuel, A., & Liberman, N. (2020). Cognitive performance is enhanced if one knows when the task will end. Cognition 197, 1 - 11. doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104189 After recently presenting at the ASIS&T 24-Hour Global Conference 2022 I have been thinking about the importance (and lack thereof) of theory in academia. Before I start telling you about the road my thoughts have led me on I want to clarify: I DO think theory can be important for research and that an understanding of the theory that previous researchers have used to make sense of similar topics can help someone conduct high quality research. That being said, I also think there may be an overemphasis on the importance of theory in academia. So let's explore my theoretical ruminations of the past weeks. I'll begin with some insights from research I've been reading to help me prepare the methodology chapter of my thesis (so the first bit might be tough to get through) and follow this with a combination of my own thought process over the last few weeks and some insights from other attendees of the conference. I conclude with my own opinions on where theory should lie in research and whether I think we do, or don't, stress its importance the appropriate amount in academia.

The word "theory" has multiple definitions, and there is not currently, nor is there likely to be in the future, a single definition accepted across all of academia. Pinfield et al. (2021 pp. 44-45) maintain that there are different conceptualisations of theory which may differ between disciplines and populations. For example, general dictionary definitions of the term were divided into at least three categories by Pinfield et al. (2021 p. 43): something abstracting reality into basic principles; something explaining or aiding understanding; and something that guides practice. In academic disciplines theory may take the form of "rigorous mathematical laws", "explanatory models", "descriptions of causal processes", "abstract account of something", "conceptual artefacts", and more (Pinfield et al., 2021 pp. 45-48). In my academic discipline of library and information sciences (LIS), the discussion of theory is often cited as lacking (e.g., Lor, 2014 p. 30). Lor (2014 p. 30) citing Anyon (1982 p. 35) states that theory and data are in symbiosis; they feed into each other to the benefit of both. A main criticism of the lack of theory in LIS is that data and patterns are collected and observed with no theory to ground them (Lor, 2014 p. 26). In essence, the argument by Lor (2014) is that without a theory to act as an explanation for why patterns exist, any data generated and analysed do not enhance knowledge. In a similar vein, Pettigrew & McKechnie (2001) suggest that in fields such as LIS, when there are no theories developed specifically for that field, then there is no way to create clear disciplinary boundaries (e.g., there is no way to tell whether a bit of research falls into the field of LIS or in the field of migration). In their research on how theory is used in LIS research, it was found that use of theory is increasing in the literature but it was unclear how large a role theory played in the actual research (Pettigrew & McKechnie, 2001 p. 70). Pinfield et al. (2021 pp. 52-53) suggest that the lack of theory identified by Lor (2014) and Pettigrew & McKechnie (2001) may be due to the usefulness of theory in the practical work of the LIS field. Unlike fields such as nursing, religious studies, and military communities of practice, there is not a significant amount of "practice theory" in LIS (Pinfield et al., 2021 p. 53). Pettigrew & McKechnie (2001 p. 69) see this in the citation practices in the LIS literature that does include theory, mainly that the citation practices of researchers isn't consistent, which may indicate that researchers recognise the importance of theory but are not aware of best practices of application. Indeed, Pinfield et al. (2021) suggest that rather than grand "theories of everything", the most useful application of theory in LIS is the use of mid-range theories which are more detailed than hypotheses but fall short of a theory meant to explain every nuance of a situation. It is in this sweet spot that a theory has some practical use, as reasons behind patterns are explained but there is space for exceptions to be made and adjustments enacted based on individual situations. Theory, therefore, is important for explanation but in the field of LIS there may not be a single unifying theory such as what might be strived for in a discipline such as Physics. The purpose for my individual ruminations about theory are based on feedback a received on a dry-run of my conference presentation. Multiple members of my research group presented at the conference, all of whom had great presentations at the conference, and we held a group meeting to practice our presentations and receive feedback the week before the conference. One member of our research group gave each of us the same advice, "Your work would benefit from including theory in the presentation". This is a good point, especially from a senior researcher, because when we conduct our PhD one of the things that you are taught is the importance of theory. Most PhD works (mine included) have some sort of theory that guides their research. As mentioned about, this theory helps them actually make sense of any patterns that occur in their data. However, on this occasion I wasn't sure that the advice about theory making the presentation stronger was the best advice. Cue three weeks of me thinking about, reading about, and trying to make sense of my feelings in my own head. In researcher terms, this might be called reflexivity. Or it might be called an emotional spiral. Potato, potahto. Anyway. The research I was presenting on hadn't been based in a theory initially. It was based on personal experience which was then explored in greater detail using the experiences of additional researchers as case studies. Theory didn't play into it, we just wanted to know "what is going on". Lor (2014) would call this naïve empiricism, and perhaps it was. However, after my time spent thinking about this, I realised that what bothers me about the emphasis on including theory in all research (and the additional expectation that the same or similar theory will continue throughout all your research) is that theory is a very "Western" concept. My reason for putting "Western" in quotation marks is a separate blog post, but for current purposes it can be considered the majority of Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America. The academy as we know it is largely based on "Western" values and thoughts and a great deal of the academy focuses on very specific outputs (e.g., published papers, with the "highest quality" journals often being published in English) and steps deemed best practice. Theory is one of these steps. My issue is not with the concept of theory, or even the application of theory in research. The issue for me is that theory is a box in which data is put. Boxes can be important. Boxes have helped humans survive, and the tendency to create and put things into boxes has continued through our evolution for a reason. However, by preemptively putting something into a box (in this case, putting a pattern found in data in a box) can keep us from considering other options. So I think theory is important to know and enact in research, but it can also limit the findings to only what we have already considered as "truth". As a senior researcher at the ASIS&T 24-Hour Global Conference suggested, it is a good idea to be aware of the multiple theories related to a research project from the beginning, but that doesn't mean you have to choose one that will fit at the start because it may not be apparent which one is best until you hit the end of analysis. In PhD research, I think it is helpful to have a theory in mind in the beginning, but this does not mean you should be locked in to this theory throughout and it doesn't mean that the process of your PhD should be repeated for every bit of research. In conclusion, then, my ruminations on theory have resulted in a vague acceptance that I have to include theory in my research but it doesn't mean I have to like it. Or perhaps, the results are an acknowledgement that use of theory is lacking in LIS research but that it is important that we make sure any theory we use is appropriate and is communicated effectively. The most important thing, in my opinion, when it comes to theory in research (in and beyond the LIS discipline) is that the academy is set up in a very specific way to consider specific outputs and types of conclusions. As researchers we must be aware of what might be missing from the way theory is created/communicated, and whether the "boxes" we use as explanation might be hiding additional truth from us. Citations: Lor, P.J. (2014). Revitalizing comparative library and information science: Theory and metatheory. Journal of Documentation, 70(1), 25 - 51. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-10-2012-0129 Pettigrew, K.E., & McKechnie, L.E.F. (2001). The use of theory in information science research. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 52(1), 62 - 73. https://doi.org/10.1002/1532-2890(2000)52:1<62::AID-ASI1061>3.0.CO;2-J Pinfield, S., Wakeling, S., Bawden, D., & Robinson, L. (2020). Open Access in Theory and Practice: The Theory-Practice Relationship and Openness (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429276842 Last year I submitted an application to attend the iConference 2022 Doctoral Colloquium, and tomorrow begins a week of meetings, papers, posters, and presentations. As the conference is completely virtual, the Doctoral Colloquium has been split into geographical regions so that none of us are forced to stay up very late (or get up very early) in order to participate. This year, students will be presenting lightning talks to each other. We each have 3 minutes to give an overview of our entire PhD project, and the option of three slides in which to do so.

While I have a 90 second elevator talk explaining the general idea of my PhD, and have given multiple 5, 10, and 15 minute talks, making a balanced presentation in 3 minutes will be a bit of a challenge. Because I'm in the final year of my PhD (see previous blog post for some musings about that), I have a lot of information related to my PhD to share, enough to almost write an 80,000 word thesis. Condensing all this information into 3 minutes in a meaningful way is not easy, and only time will tell how well I've done so. You can view the slides that will accompany my lightning talk on Slideshare here: www.slideshare.net/RachelSalzano/iconference-2022-doctoral-colloquium-presentation. If you're interested in the work I've done, or are interested in participating in my workshop/focus group method with people with lived experience send me a message and I'm happy to talk! You can contact me through the contact form on this website, by emailing me at [email protected], or find me on Twitter as @librarygryphon. I am now halfway through the third (and supposed to be final) year of my PhD. Time has been a strange concept over the past two and a half years, partly because of a global pandemic, partly because I'm getting older, and partly because time is a human construct anyway (but I won't get into that argument here). I have somehow become one of the "senior" PhD students in my research centre, one of the people other PhD students ask about which form to fill out, or at what point to do something. Alternatively, I'm the PhD student who jumps in and encourages others to not be so hard on themselves, or not take on too much, or choose one thing now because there will be time later, and for some reason I am listened to. I'm sure part of it is because I have a loud voice and I like to talk, but part of it also seems to be because I'm somehow one of the ones closest to finishing. And I don't know how that happened.

I don't feel like I should be in the final year yet. I feel like I'm still as unsure of what I'm doing as I was the first day. But at the same time I have deadlines (a lot; some of which I'm avoiding right now by writing this blog post), deadlines that only really happen during the last year of a PhD. Like completing transcription and data analysis for one of the main methods of the project. Or like trying to get a part of the project you really want to complete off the ground (if you are interested in my art exhibition project, go to cultureandlibraries.weebly.com or email me at [email protected]) even though you know if probably won't make it into the actual thesis. There's a lot of pressure being in the final year. Being a role model (or at least not someone who scares other students away) is tough when you're feeling frazzled with deadlines that can't really get pushed back any further. Meeting those deadlines becomes even more important because you no longer have "next year" to go to conferences, or write that paper, or complete data collection. You also somehow have to write a thesis. So there is a great deal of pressure being a third year PhD student, much of it internal pressure we put on ourselves. So what do we do when there's so much pressure? What I'm trying to do is take a full day off from PhD work every week. The work will still be there, but removing myself from the work keeps the pressure from becoming too much. We'll see how I continue to get on in the rest of my third year, but so far this seems to be working. So for the rest of the students (third year PhD or not) out there, keep working, but make sure to take time for yourself, regardless of how much you have to do. It is nearing the end of the term and I am getting very close to the cut-off date for my current data collection method. Right now I am interviewing gatekeepers (people who work with and support refugees and people seeking asylum). The questions of my interview are about culture and service usage. While my research focusses on the relationship between culture and the use of public libraries, I'm interviewing gatekeepers not directly associated with public libraries. This is to help address a gap in the current literature, that much of the research is from the perspective of public libraries as service providers. I was hoping to address the gap by speaking to people with lived experience, but that hasn't been possible so far (don't worry, I'm still hoping to work with lived experience through my art exhibition project). By interviewing gatekeepers who are not directly associated with public libraries, I can partially fill the gap by including perspectives other than that of the public library.

In research there is usually a goal for a certain number of participants. There are many reasons, some of which relate more to quantitative research (e.g., is this result significant) and some which relate to qualitative research (e.g., have I reached saturation). In the case of my research, my goal is to reach 30 interviews. At the moment, I have reached 28 interviews and am searching for my final two (or more if enough people want to participate). It is the final push for this method in my PhD, and I'm really wanting to reach that minimum target of 30 interviews, so if you work with or support refugees or people seeking asylum in the UK and want to participate in my research, please contact me through the contact form or by email [email protected]. And keep your eye on this page for more updates on the project! While not a method in my initial plan for my PhD, I find myself analysing documents in order to explore how often, and in what manner, public libraries are considered in official documentation related to the integration of refugees and people seeking asylum in Scotland. Once I finish data analysis, I will be writing up the results in a findings paper that will be submitted to CoLIS 2022, taking place in Oslo, Norway. I'm hoping that I will be able to write a full paper for that conference, as thus far I have only submitted short-papers and posters.

The process of analysing a document is both similar and dissimilar to analysing an interview. While similar methods can be used for both (like the thematic analysis I am using), I find that analysing a document is like analysing an interview you didn't conduct. Though you have the words that were said, you don't have any knowledge of inflection, tone, or the type of conversation. As has been told to me in undergraduate psychology modules, public speaking trainings, and all-staff meetings, a large amount of human communication is based on non-verbal cues. Losing those non-verbal cues means losing some of the meaning of a conversation. You have to take the words at face value and hope you're not misinterpreting something. Analysing documentation feels very similar to deciphering a conversation without non-verbal cues. What does this mean for my analysis? Well, it means that what I find is based purely on what was written down and the way that I view the world. My biases and background will always have some bearing on what I think a piece of data is telling me. However, when I don't have additional information about how something has been said, I am made even more aware of how my own interpretations drive the conclusions of my research. The field of academia often emphasizes objectivity, and in academic writing findings that are published often have to be framed as certainties. If the process of analysing documents has taught me anything, it is that those of us who write research need to always keep in mind just how certain we are that conclusions mean what we think they mean. It isn't just readers of research that need to take everything with a grain of salt, those of us who write research should also take our own outputs with a grain of salt. PhD research is interesting in more ways than one. Not only do you get to, hopefully, explore a topic you love in great detail, you also have to be able to adapt your exploration to what is happening around you. Case in point, the Covid-19 Pandemic has had a large influence on many PhD research projects, including my own. Due to restrictions I haven't been able to meet people in person until recently, and so my research has undergone quite a few adjustments. I now have four methods running at the same time, three still searching for participants. Take a look at the different methods I'm using below, and please do share with your contacts and take part yourself!

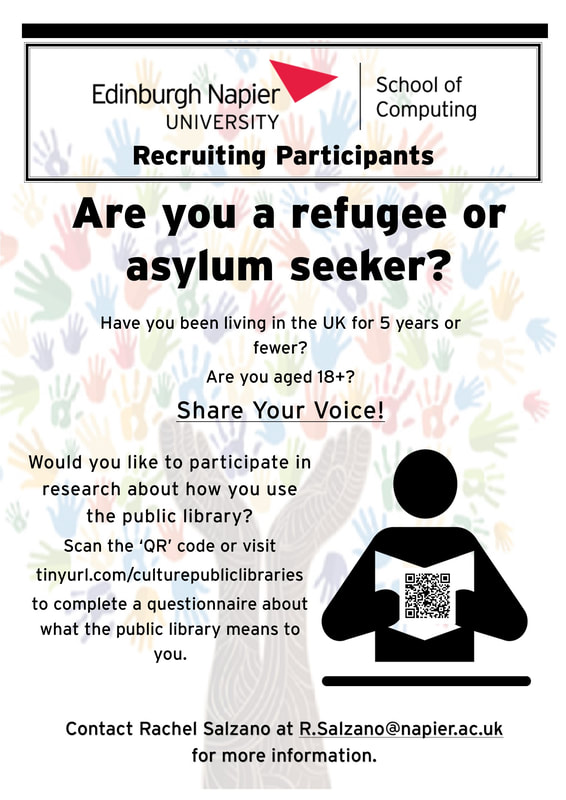

My PhD research is about how culture influences the use of public libraries by refugees and people seeking asylum (forced migrants). It is meant to help illuminate why certain resources are used in specific ways and whether they are actually the best resources to provide support for forced migrants or if they are just the next best option. The work is framed around the needs, requirements, thoughts, and experiences of forced migrants, rather than current public library provision. The study is mostly being conducted online, though in person interviews can be conducted based on your comfort level. There are three branches of this research: questionnaire with follow-up interview with forced migrants; art exhibition with artwork from forced migrants; gatekeeper interviews with individuals who work with and/or support forced migrants. For the questionnaire/interview, participants complete a fully anonymous online questionnaire. Participants can provide their contact information if they would like to be contacted for a follow-up interview. Follow-up interviews will be conducted based on results from the questionnaires. I am using this method to learn from the lived experiences of forced migrants about how and why they use the public library in the UK and country of origin. For the art exhibition, participants can submit a photograph or piece of artwork in any medium which represents why they use the public library (view the art exhibition website here). The art elicitation will result in a public art exhibition showcasing forced migrant voices (with prizes for the artwork and stories). The submissions will be physically displayed in a library in Edinburgh as well as be displayed online. I am also interviewing individuals who work with or provide support for forced migrants (gatekeepers). These interviews (via Microsoft Teams, telephone, or in person dependent on participant comfort) to triangulate data gathered via other methods. Gatekeepers can be currently working with/supporting forced migrants or have done so in the past. Covid-19 has affected quite a bit, so even if you haven't been doing anything since B.C.E (Before Covid-19 Era) I would still love to chat with you. Contact [email protected] to set up an interview or use the contact form on this blog site. As a final method, I am reviewing the official documentation 22 local Scottish Authorities hold regarding forced migrant integration and resettlement. By looking at the policies of different local authorities I will be able to look at how life experiences of forced migrants and gatekeepers match up with what is officially documented as important. I hope this comparison will result in recommendations that will help library staff, local governments, and other gatekeepers provide the best support to forced migrants. My methods have changed and adapted as I've gone through my PhD, which has taught me a lot about research and myself. I am still in need of participants, so if you or anyone you know is interested in helping me learn what is actually needed to support refugees and people seeking asylum, please participate in the method that matches you! My PhD is currently in the empirical stage, where I am searching for participants and collecting data. Based on the findings from my literature review my research is taking two forms. One is a more traditional mixed methods approach where a quantitative questionnaire and qualitative interview are combined: tinyurl.com/culturepubliclibraries. The other is an art-based approach, which will result in an art exhibition showcasing the voices of refugees and asylum seekers. To learn more about the art exhibition work, feel free to visit: cultureandlibraries.weebly.com.

The poster included at the beginning of this post is a distilled version of my call for participants to complete the questionnaire (during which they can volunteer for a follow up interview), but there's some detail that can't be fit into a pretty poster. The questionnaire itself is available in nine languages: Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Swahili, Thai, Turkish, Urdu, and Vietnamese. The questions themselves cover how participants used the public library (i.e., what resources, how often, and why) in their country of origin, how they use the public library in the UK, and cultural background. Most of the questions are quantitative (i.e., participants choose out of a set of options) but some allow participants to write out their thoughts. The data from the questionnaire will be used to find patterns in cultural background and how/why participants use the public library. Participants can also volunteer to take part in a follow up interview. Live interpretation will be available from qualified interpreters for participants who request an interpreter. The interview will be based on the data being returned from the questionnaire, and will gather qualitative data (i.e., participants' won't be given options to choose from, but will be asked to answer in their own words and may be asked additional questions). The questions of the interview will also include questions about how participants use the public library, in both their country of origin and the UK, and about their cultural background. The data from the interview will be analyzed for patterns and confirmed with participants where possible. This member validation will help make sure that the patterns researchers see match with the actual thoughts of participants. It is hoped that his research will provide a perspective that is not based on what libraries currently provide, but on what refugees and asylum seekers need libraries to provide. There can be a disconnect between what library staff think is needed and what is actually needed. Understanding the relationship between culture and use of the public library can help bridge the gap. Thank you to everyone who shares this call for participants with your network and signpost to the questionnaire. |

A Second Blog Page?This is the part of the blog specifically about my PhD. It will include updates, musings, and advice. Archives

August 2022

Categories |

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed